It's important to note that generalisations about the popularity of abstract art in African art and the diaspora can be challenging because artistic preferences and styles are diverse and vary across regions, cultures, and individual artists. However, there are historical and contextual factors that may have influenced perceptions of abstract art in this context.

This article will explore the complexity involved in understanding abstraction from the continent and its diaspora and will give examples of artists who work well in this arena.

The influence of European colonialism played a significant role in shaping artistic perspectives in Africa and the diaspora. Traditional art forms, often characterised by figurative and symbolic representations, were sometimes marginalised in favour of Western artistic styles.

Many traditional African art forms are deeply rooted in representing the human figure, animals, and symbolism that often convey cultural, spiritual, or social narratives. The emphasis on representation and identity in traditional art might contribute to a preference for figurative work rather than abstraction. The most prominent modern painters from the continent, such as Ben Enwonwu in Nigeria, Valente Malangatana Ngwenya in Mozambique and Irma Stern and Gerard Sekoto in South Africa, all worked in a figurative expression, as did most of their lesser-known peers. At the most basic level, this may be explained by the fact that, in the 20th century, African socio-political reality absorbed the energy that might otherwise have been directed at aesthetic debates about abstraction. Figurative and representational art may be more aligned with conveying specific cultural meanings and histories, making abstraction less prominent in certain contexts.

Irma Stern, Summer Morning in Madeira, 1950, Oil on board, 62 x 49.5 cm. Image source: Piano Nobile Gallery

Ernest Mancoba is a prominent exception. He became part of the CoBrA group in the late 1940s after moving to Europe from South Africa to escape increasingly restrictive racial policies. Throughout his life, his imagery, distilled from the form of objects such as theBakota funeral effigies of Gabon, gradually dissolved into a field of marks. Mancoba created his first painting in Paris, an abstract work titled Composition in 1940. His move into abstract painting was partly motivated by his resistance against the perception of African art as ‘primitive’ by the European art world.

Over time, as artistic movements and preferences evolve, there may be a tendency to associate certain styles with authenticity or tradition. This can impact the reception and popularity of abstract art, which might be perceived as departing from established norms. For example, South African artist David Koloane was criticised by white art dealers when experimenting with mediums such as collage or abstract art. His art was seen as ‘un-African’ implying that Koloane was just a misguided imitator who produced ‘unoriginal’ European art.

David Koloane, Untitled (lights in traffic I), Oil on canvas, 76 x 51 cm. Image source: Goodman Gallery

While today artists might feel more free to explore personal and formal concerns than ever before, there is a persistent demand from curators and critics that African art be "about’" something.

For example, El Anatsui, conceivable Africa’s most prominent abstract artist, is often discussed in correlation to recycling, and its formal qualities related to African textile patterns. It's essential to recognise that these factors are generalisations, and there are many artists within Africa and the diaspora who engage with and produce abstract art. While the artist does use repurpose of alcohol bottle caps and other discarded materials of production, trade, and consumption into large-scale hanging installations, Anatsui’s narrative is concerned with the overconsumption made prevalent in Africa during the colonial expansion of Europe and the Americas.

As the art world has globalised, there's a growing recognition and appreciation for diverse artistic expressions, including abstract art from African and diasporic artists. Contemporary artists are challenging stereotypes and exploring a wide range of styles to communicate their unique perspectives and experiences. Africa and Abstraction: Mancoba, Odita, Blom Published by Stevenson in 2013 is a catalogue that shows the work of two contemporary African abstract painters, Odili Donald Odita and Zander Blom, alongside their most significant predecessor, Ernest Mancoba. Nigerian-born Odili Donald Odita, has been working as an abstract painter since the late 1990s and has defied these ‘traditional’ expectations that Anatsui has been subject to. More recently, the paintings of Zander Blom have played a central role in the re-evaluation of the potential of abstraction in South Africa.

Ernest Mancoba, Untitled (1951), oil on canvas, 60 x 49.5 cm. Image Courtesy of Esatet Ferlov Mancoba, Copenhagen.

And like Odita, Burundi-born, Johannesburg-based artist Serge Alain Nitegeka participates in a dialogue with the dynamics of geometric abstract shapes and, in his drama of the manipulation of tilted planes, of geometric, coloured shapes engaged in a Constructivist tradition. Much of Nitegeka’s inspiration comes from a fascination with the built infrastructure of Johannesburg itself, the highways and buildings and the basic structure of its urban landscape, in other words, contemporary Africa.

We also see that the value of abstraction in African art is immense. A 2008 painting by the Addis Ababa-born, U.S.-based artist Julie Mehretu has fetched $10.7 million at a Sotheby’s auction in New York. The Ethiopian artist has broken the record for an African artwork at auction at Sotheby's Now Evening Auction in New York, her abstract painting Walkers With the Dawn and Morning sold for $10.7 million — surpassing the previous record she set a month before. Often the artist blends heavy layering to create abstract imagery, drawing inspiration from graffiti, city maps, and comic book graphics. Drawing from calligraphy and the rich heritage of Nsibidi reflects a profound engagement with both history and modernity, Victor Ekpuk, a pivotal figure in the African art scene, has not only redefined the boundaries of abstract art but has also played a significant role in revitalising traditional visual communication systems.

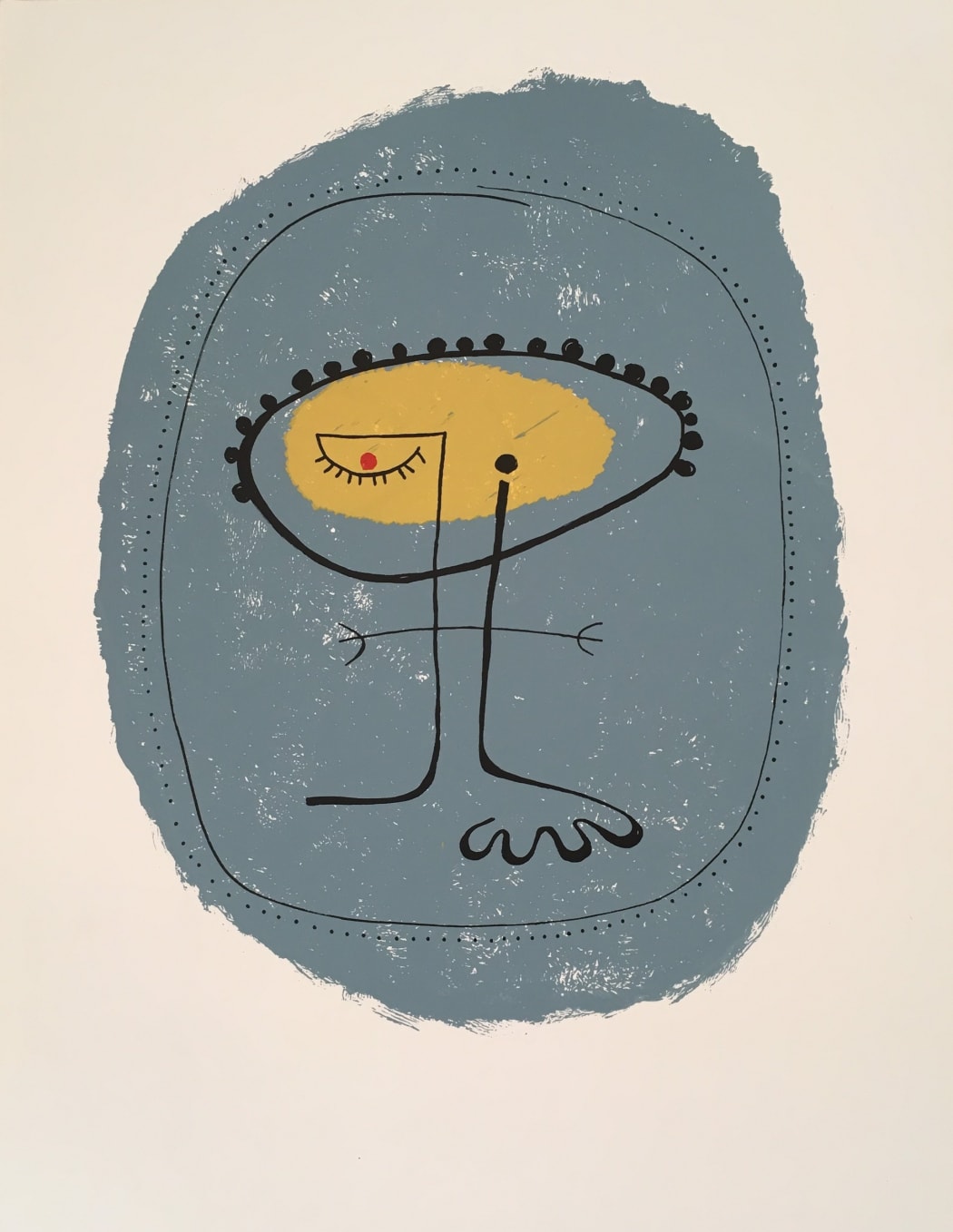

Victor Ekpuk, Head 4, 2015, Acrylic on panel, 45 x 48 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

Contemporary African abstract art has made a significant impact on the global art scene, garnering international recognition and influencing artists worldwide. Several factors have contributed to this growing prominence but mainly international exhibitions and recognition. Contemporary African abstract artists have been featured in major exhibitions and galleries, such as the Venice Biennale, the Dakar Biennale, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. These showcases have introduced a global audience to the beauty and complexity of African abstract art, helping to elevate its status within the art world.

This article has demonstrated how artists undermined the preference for figuration as innately ‘African’ and how many African artists are not necessarily against figuration in art but they are rather working in a manner that is opposed to the reductive labels that made the work of abstract artists less valuable in comparison with the work of other styles.