With a new show ahead, and retrospectives of her illustrious career, Helen Sebidi remains remarkable and worthy of admiration.

In the vast tapestry of the art world, certain threads are woven more prominently than others, casting shadows that obscure equally brilliant hues. Helen Sebidi, a modern master hailed from South Africa, emerges from the folds of this tapestry, her vibrant strokes and profound insights challenging the established narratives of artistic recognition. I visit her at her Parktown home on an overcast, lightning filled, grey sky Joburg afternoon – over a cup of tea we share conversation.

Sebidi shares her life story and occasionally I feel comfortable to share mine – recent times have not been so easy but our conversation assures me that while it never is, it is worthwhile. Despite the tumultuous conditions, what unfolds is a warm afternoon, over tea and eet-sum-mor the great artist emerges as an even greater personality – elder wisdom, grace, and honestly emerge.

In my chit-chat with Sebidi – Nkgono I call her, her words reverberate with the weight of a lifetime spent navigating the corridors of artistry, identity, and legacy. Though we have shared multiple conversations, and we are relatively familiar with one another, we begin as we always do – at the start. Sebidi reflects on identity, her relationship with he ancestors, her relationship with her grandmother and the resistance to colonialism, apartheid and their legacies.

It occurs in this convection that there has been a struggle – perhaps not hers – in decolonial conversation – to recognise Sebidi within the pantheon of modern black artists in the canon of a national South African art. Initially pigeonholed as an "ethnic traditional painter," her journey mirrors that of many artists whose voices are muffled beneath the clamour of dominant narratives. It would be remiss to pretend that this conversation, regarding Sebidi as a modern master, has not begun and gained traction.

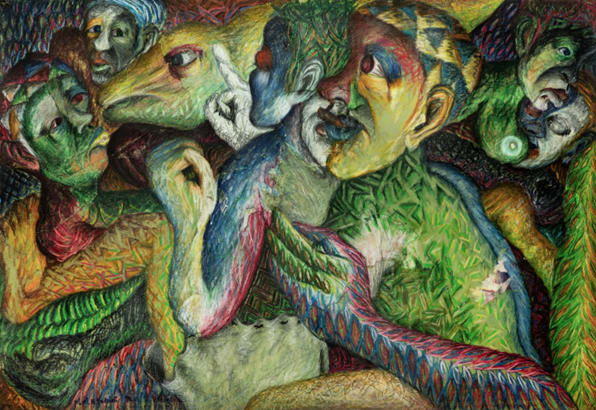

Mmakgabo Mmapula Helen Sebidi, ‘Mafatsi A Tlhakana (The Meeting of Different Realms)’, 1991, pastel on paper, 147cm x 109 cm. Courtesy Everard Read and Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi

Central to Sebidi's narrative is her relationship with John Koenakeefe Mohl, through his mentorship, Sebidi found not only artistic guidance but also a profound sense of belonging within the artistic community. "Only recently are they saying if John Mohl is a modern master, then I am too.” This highlights the ongoing discussion with recognition within the art world and the shifting perceptions of her identity as an artist. "I think for me they just have to speak the way they want. I don't mind," Sebidi says. While they are certainly not the same, this year I encountered a conversation which began to promote the work of Dr Esther Mahlangu as a modernist.

Following the ongoing retrospective at Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town the artist's work is now recognised by ignorant audiences as a “highly coded expression of Ndebele resistance to the incursion of Boer settlers onto their ancestral lands.” Furthermore, the exhibition at Iziko paints the artist as a “modernist painter, and Warholian entrepreneur.”

Mmakgabo Mmapula Helen Sebidi, ‘Kamogelo ya Moya’. Courtesy Everard Read.

Yet, despite Moore's recognition as a modern master, Sebidi found herself relegated to the sidelines, her voice drowned out by the echoes of a biased canon – not Mohl’s fault and not hers either. “Then they used to say that I was an ethnic-traditional painter. But only recently are they saying "If John Mohl is a modern master, then I, Helen Sedidi, am also a modern master."

However, Sebidi's story is not one of resignation but resilience. Her assertion that she is "out for them to harass themselves" speaks volumes about her refusal to be defined by external labels. Instead, she embraces her autonomy, carving out a space for herself within the ever-shifting landscape of artistic discourse.

Much recognition has followed Sebidi in the last few years: in 2019 Portia Malatjie curated the acclaimed Batlhaping Ba Re!, an exhibition featuring paintings, etchings and sculptures from a career spanning five decades. This year, opening on 6 April, ‘Keiaha Ntlo E Tsamayang’ (The Walking House), a compelling exhibition co-curated by Gabriel Baard and Prof. Kim Berman will open at the University of Johannesburg. Nevermind that Helen Sebidi was the first black winner of the Standard Bank Young Artist Prize (1989).

The artist's practice continues to evolve, a testament to the practice that has reverberated across generations – born decades after Sebidi, the artist's work was taught to me in high school and has echoed through my journey as a cultural worker. Her journey is not one of stagnation but of constant reinvention – reconsigned across time periods for her mastery in multiple mediums, across multiple generations.

Mmakgabo Mmapula Helen Sebidi, ‘Keiaha Ntlo E Tsamayang’, pastel on paper. Courtesy Everard Read and Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi.

As the afternoon sky rumbled loudly with the promise of rain, Sebidi muses on the notion of finishing one's work only upon departing this world, a reflection that transcends the boundaries of artistic practice. Through her art, Sebidi grapples with the ephemeral nature of existence, seeking to leave an indelible mark on the fabric of time. Yet, amidst the weighty themes that permeate our afternoon-log conversation, there has been an undercurrent of warmth and humour. Our conversation unfolds with a playful cadence – I take a walk twice or thrice through the garden, view her garden, greet the kittens and put the teacups away in her old-school kitchen. Again, this homeliness and its familiary strike me.

As the conversation draws to a close, there is a sense of continuity, a promise of future encounters and shared experiences for this conversation. During the visit I’ve patiently paged through the out-of-print books – Sebidi invites me to revisit her and borrow a book and kindly note that this is an ongoing dialogue between artist and her admirer.

To end this article, Sebidi's story is not just about art—it is about the resilience of the art, the power of self-definition, and the enduring legacy of those who dare to defy convention. Through her vibrant canvases and profound insights, she invites us to embark on a journey of discovery, one that challenges us to question, to reflect, and to embrace the beauty of our shared humanity.