Bâ Simba speaks slowly, intentionally, and every word that comes from his brain seems to be hand-crafted and specifically selected for the sentence he wishes to convey. His words have a weightiness and authority that belie his humble nature, but they are well-suited to his body of work, a painterly practice that employs vivacious colour, strong line, and profound storytelling, in ample measure.

The Broom in Every Room (2022) by Bâ Simba. Acrylic, Ink, and Collage on Panel.

Perhaps the artist’s eloquence comes from his dedication to education from an early age, in the village of Kindu, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where he and his siblings would walk eight miles just to sit outside and eavesdrop upon the lessons in the schoolhouse. Later, his way with words manifested itself in not one, but two, awards in a national essay and speech writing competition—the same that was won by Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. Today, Bâ Simba’s words are mostly visual, translated into his rich visual artistic practice that combines geometric patterns, found materials, references to African art history, and Pan-Africanism. The mission? To reclaim the discourse around contemporary African art—specifically Central African Art—which has for too long been under colonial power and influence, and to introduce a Renaissance of Congolese contemporary art and Bantu culture through the powerful story telling in his paintings.

In an interview with the artist, Vienna Kim asks Bâ Simba more about his practice, his inspirations, and the story he wishes to convey through his art.

P54 : Let’s start with the formal aspects – the materials you use. They are quite unconventional. You often use doors, chairs, or tables as the canvasses for your work.

BS: First, I think it started with the fact that I did not have enough material, so I found beauty in things around me outdoors. I grew up in an area that was so poor that people would say it’s dangerous. These areas are not all dangerous, they are often just deprived of means. So I would see abandoned cars, and I thought that they were beautiful and that they could be rehabilitated, they could be painted, like how our ancestors would do on pyramids and trees. I came to an understanding that the ‘canvas’ is not necessarily a conventional, professional canvas you see in galleries, but the canvas is my world—my clothes, or an abandoned door.

The seat of memories by Bâ Simba. Acrylic and collage on Leather recliner.

P54: And do you think this use of unconventional base materials changes the relationship of the object with the viewer, maybe even a potential collector? What kinds of feelings or thoughts do you want people to have with your work?

BS: I hope that my audience has the same feeling I have when I work on the materials I paint on. It started as a means, and eventually an aesthetic choice, but now it’s a storytelling. For instance, I painted a story on a door, because it was the only way that story could be told – a multidimensional work. I pursue material now because it matches the story I’m going to tell. And I hope that people that look and interact with my stories get to feel that.

Uhuru means Freedom (2022) by Bâ Simba, Acrylic, Ink, and Collage on Panel.

P54: A lot of your practice is rooted in storytelling, both in your personal story and also with the Pan-African history you want to honour, pay tribute to, but also extend in your own way. Where do your stories stem from? How do you see the connection of your own story with Pan-Africanism more generally?

BS: I think my work is driven by the need to connect my ancestors to the progeny today. And that has always been the goal for Bantu art since the beginning of history. We were colonized by the Belgians from 1885, up to 1960. Everything was erased from our memory and cultured identity, their sense of beauty. No other country on Earth went through the re-Africanisation of the people, so that we could get some sense of ourselves. The goal was to make sure we started to create things that would link our ancestors, who went through so much, to the progeny that needs to understand who we are, and what we need to champion today. That's what I do. That's what I pursue.

Mémoire du Premier ministre (2022) by Bâ Simba, Acrylic, and Ink on Canvas

P54: As you know, there’s the Zaire School of Art from the 1970s, and I think it’s so interesting how you state on your website that this is the only artistic movement from the Congo that is really known about, and you want to expand upon it, but also move on from it. That’s your mission for Central African art. Can you tell me more about your ideas, ambitions, or hopes in the continuation of this art history?

BS: This kind of goes with the need to tell those stories that link our ancestors to the progeny. The stories now start to align—all these untold stories that are personal, like my story, and the people that grew up around me. That is part of the storytelling; the story of the community that raised me and champions me and inspires my art, and also of the world because the African story is a universal story. All that being said, our Renaissance was interrupted. We did not get to see it come to fruition and we only hear about the confiscated artworks that were taken from colonial times, and generations couldn’t learn from it. I feel like every young contemporary African artist needs to expand from those movements you mentioned, with the goal to make sure that this artistic delay is over and we pursue greatness from where is started, because then we have an endless source of inspiration. We already have a source. We just need to look back there.

Genesis (2022) by Bâ Simba. Spray Paint, Acrylic, and Ink on Canvas.

P54: I once read a quote by Nigerian artist Dennis Osadebe that the term ‘African art’ was ‘lazy’. He thought it was a terminology that people would throw around to cover such a broad spectrum of art, and people weren't being specific enough or making the effort to really zone in on what kind of art that they were trying to talk about. Do you agree that the term ‘African art’ is a lazy one?

BS: It’s interesting, and I find his statement to be correct. Which is heartbreaking, because generations now turn away and miss out on a lot of inspiration. As I said, we need to elaborate on that. We pay attention to other things that do not really help the events, the movement of arts, and the disciplines within the term African art. ‘African art’ is a term that is thrown around like, ‘I go to Africa’, ‘I've been to Africa’ or ‘African music’. But there are chambers, chapters, specifics within this large, rich culture.

P54: You live in Los Angeles today, and you actually had a show going on in September 2022. Could you tell me more about this exhibition?

BS: After my first show [Global Migrations, 2021], what I wanted was one thing: the luxury of time. I had this vision to craft a few series that I wanted to present to the world. We spent eight months crafting the work that we exhibited in September. I’m so happy with how everything is presented from trusting and benefitting from the luxury of time. We found the right place, the right people to enjoy and install the work. And what is the most important part is: ‘How do people interact with my work?’ You just see people from different communities come and enjoy the work, watch them be spoken to by the content of the work. I cannot wait to show my work in Los Angeles again and around the world, looking for more opportunities to show what we have, and present the next series. We’re already crafting the next session.

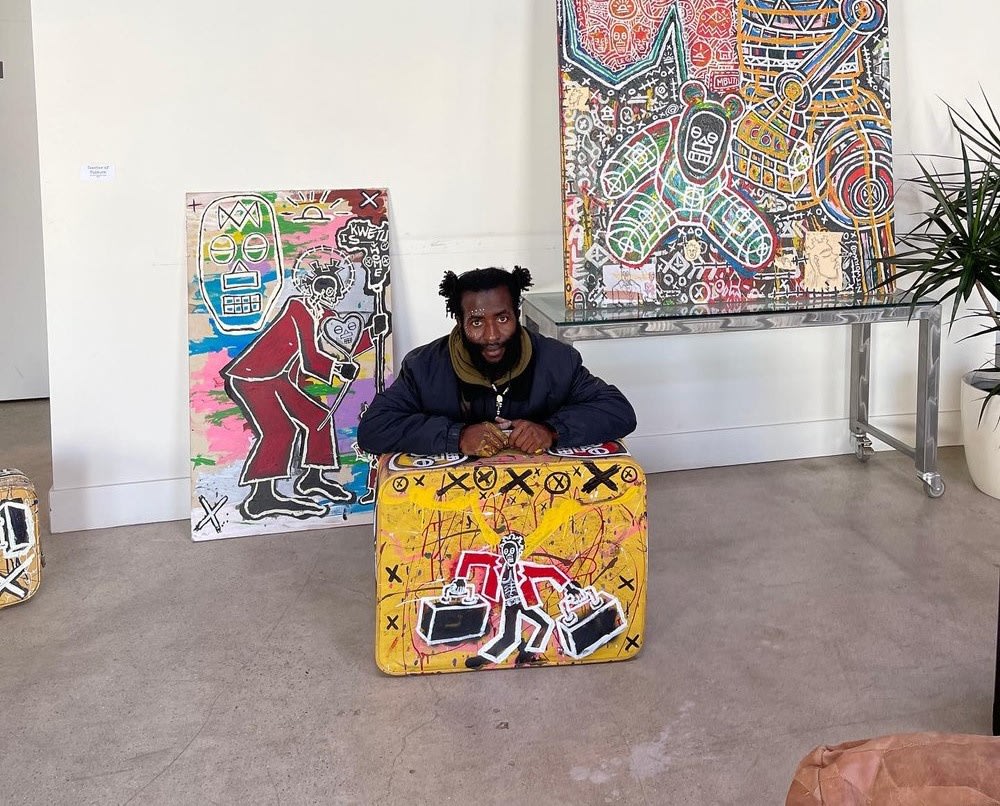

Exhibition view. Image courtesy of the artist

P54: On that—if you’re allowed to reveal this information—what kind of body of work are you currently crafting at the moment?

BS: Do I need to reveal this? [Laughs] I think at the right time, it will be presented