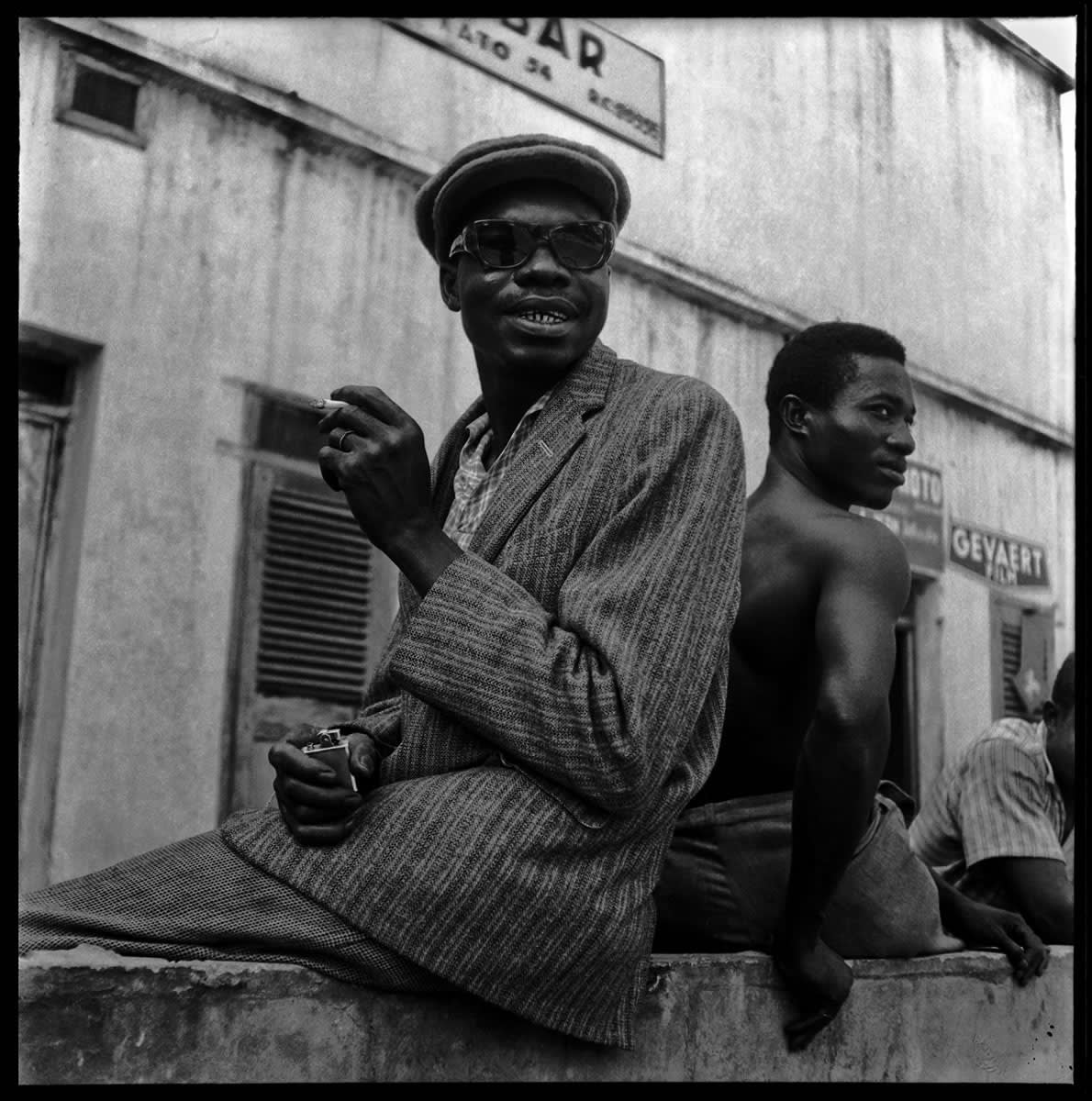

Africa and its global diaspora have met the medium of photography in all its complexities. From a colonial and ethnographic tool, photographers such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, Jean Depara, Sanlé Sory, Mama Casset or James Barnor embraced the medium along the advent of independence. Often mentioned as the forerunners of African photography – one should be cautious with such statement – they have produced a distinctive body of work – black-and-white photos, staged portraits, documenting style. The enthusiasm proper to the period of independences with its promises of social and individual emancipation stands out of this body of work. The popularity of photography on the continent came with the accessibility to the medium and to an array of modern commodities. Those forerunners speak to a specific moment in time and in a given context – West & Central Africa in this case.

Jean Depara, Night & day in Kinshasa © The Eye of Photography

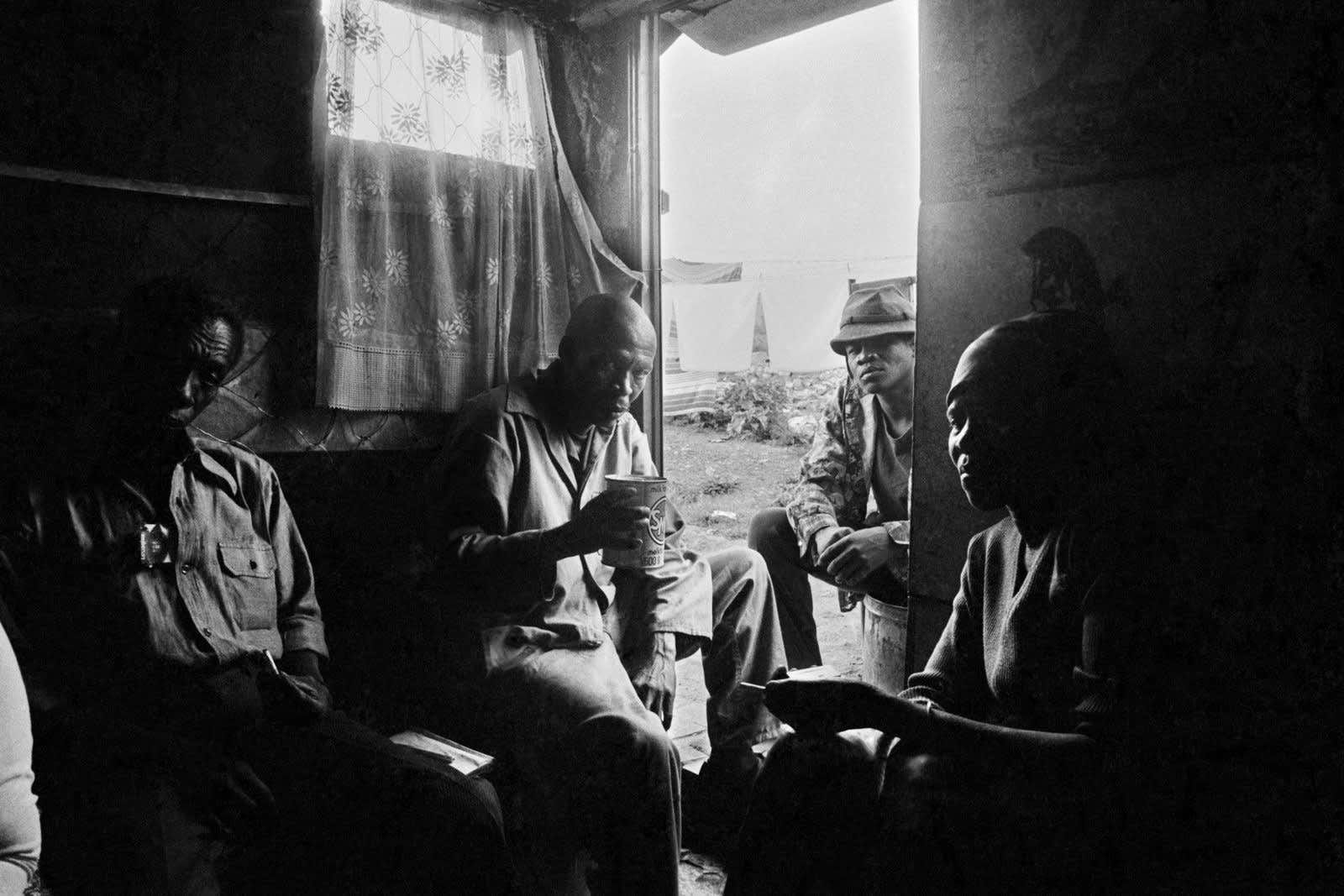

Thousands of kilometres away, in South Africa, David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole or Santu Mofokeng’s camera captured neither the celebratory nor the glamorous, but the realities of apartheid and South African society at the time. Their black-and-white shots bring to the fore the everyday life, societal and community matters while the light, the contrast(s), the shadow(s), the angle and the texture infuse some poetry and spirit to their images. They have been a great source of inspiration in their country and for contemporary African photography.

Santu Mofokeng. 1985. Chicken Farm Shebeen – Rockville. Series: Townships. © The artist. Courtesy the artist and MAKER/Lunetta Bartz, Johannesburg

Gradually, as the heydays of independence movements were giving way to postcolonial states of affairs, visual representations in African photography opened a window on the postcolonial condition. Holding to the portrait – a lasting visual trope in this photographic tradition – photographers turned the lens onto themselves in an introspective and critical gesture. This individual and collective postcolonial condition has much to do with the burdensome heritage of colonialism and identity politics. The joyful and popular aspect of those early portraits was later met with a more nuanced artistic approach. Carrying on the tradition of studio photography, Samuel Fosso (b. 1962/Cameroon)’s self-portraits illustrate the opening up of the practice to self-expression, performance-based, and critical – at times political – compositions. In this regard, one can also think about the work of Rotimi Fani-Kayode.

Samuel Fosso. 1976 & 1997. Self-portrait & Le Chef (qui a vendu l’Afrique aux colons). © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Jean Marc Patras/Galerie

From the mid-60’s onwards, photography in Africa and its diaspora built up on that legacy, keeping a documenting and social agenda, away from the stereotypical and degrading images produced by mass-media. That period saw photographers pushing the boundaries of the medium and finetuning their visual processes, increasingly conceptualising their work as fine art.The Harlem-based Kamoinge collective, that was active in the second half of last century, deemed photography as an opportunity to own everyday black life’s visuality in all its beauty, complexity, poetry and timelessness. Those decades were times of globalisation, cross-cultural exchanges, and rapid urbanisation in Africa. These phenomena surely influenced photographers’ perception and their subject matters. Technological and digital developments, artistic exchanges and rigorous practice opened up the scope of contemporary African photography.

In the exhibition In/sight : African Photographers, 1940 to the present (1996), and later Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (2006) – both presented in New-York –, the late curator Okwui Enwezor outlined several trends in the development of photographic practices in Africa, stressing the importance of an inside perspective on African realities. Snap Judgments was organised around four main themes: urban formations, landscape, history and representation, and the body and identity. These themes somehow bridge the realisations of early studio and street portraitists and the postmodern and postcolonial visual culture that follow, to offer a comprehensive framework for African photography. They are in no way exclusive or conceptually limiting.

What contemporary practices now display is a multidisciplinary approach and understanding of the medium. Given the variety and the richness of the experiences and contexts in which African or diasporic subjectivities are thriving, and the issues pertaining to this community, contemporary photography is breaking new grounds. Complementing an already socially engaging and documenting style, it has met fashion, architecture, the archive, collage, drawing, performance, technology, installation or craft in innovative artistic ways – e.g. the Photographic Collective.

Delphine Diallo, 2011, Highness Hybrid 8, © Delphine Diallo, retrived from https://pavillon54.com/artists/56-delphine-diallo/works/246-delphine-diallo-highness-hybrid-8-2011/

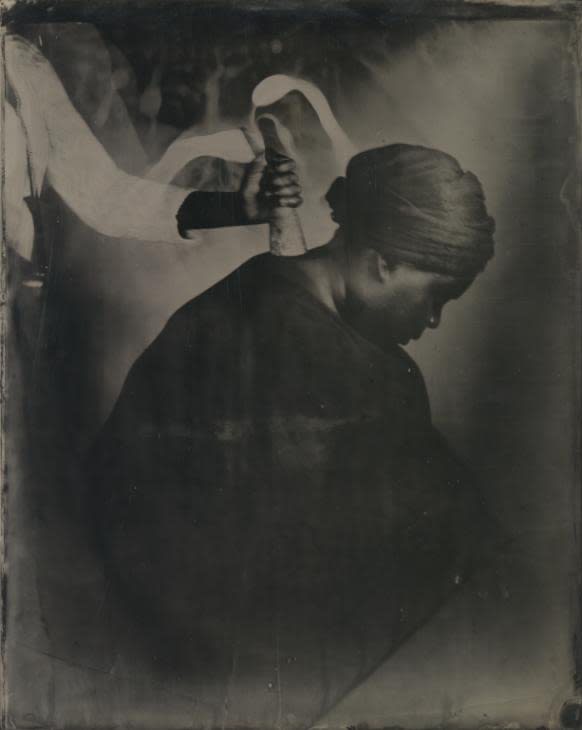

In a decade (2015 – 2024) that has been proclaimed the International Decade for People of African Descent by the General Assembly of the United Nations, visual explorations alluding to ancestry, notions of memory, cultural heritage, nostalgia, folklore or spirituality are increasingly constitutive of contemporary African photography. These notions somewhat appeal to the various techniques and textures that photography involves, photography being a prism on our existence.

Khadija Saye. 2017. Nak Bejjen. Series: Dwelling: in this space we breathe. Photograph, wet plate collodion tintype on metal © Estate of Khadija Saye - Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/saye-nak-bejjen-t15140

It would not be wise to study contemporary African photography in a traditional, linear and defining fashion, or as a definite whole. As much as the photographer’s subjectivity, existential position and social realities have evolved over the past decades, contemporary visual outputs and insights have known the same fate. Testimony of the abundant and multi-layered creativity that African and black subjectivities entail in the contemporary, photographic practices of Africa and its global diaspora defy any classification or border.

Festivals such as Les Rencontres de Bamako, Addis Foto Fest or LagosPhoto, and initiatives such as the Cap Prize, the Market Photo Workshop, The African Photography Network, Photo: or the Nuku Studio have incubated and exposed the talent, and the expensive visual trajectories of contemporary practices.

If you were still predominantly understanding African photography through the lens of early practitioners, or want to have some fruitful insights into its developments, the following two recent issues edited by Ekow Eshun will open up your perspective on the subject:

- Africa State of Mind – Contemporary Photography Reimagines a Continent (2020) by Thames & Hudson

- Africa 21e Siècle – Photographie Contemporaine Africaine (2020) by Éditions Textuel

Also :

- Platform Africa (2017) by Aperture Magazine (Summer Issue)

- https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/photography-africas-most-popular-art-form-10519/

Malick Kebe, God of Water, © Malick Kebe, retrived from https://pavillon54.com/artists/58-malick-kebe/works/456-malick-kebe-god-of-water/